What is Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis (LCH)

Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis (LCH) is the most common of the histiocytic disorders and occurs when the body accumulates too many immature Langerhans cells, a subset of the larger family of cells known as histiocytes. Langerhans cells are a type of white blood cell that normally help the body fight infection. In LCH, too many Langerhans cells are produced and build up in certain parts of the body where they can form tumours or damage organs.

Most data support the concept that LCH is a diverse disease characterized by a clonal growth of immature Langerhans cells, that in more than half the cases have a mutation called V600E of the BRAF gene and related mutations in some other cases. V600E is found in tumours such as melanoma and thyroid cancer.

There has been some controversy about whether LCH is a cancer, but it is classified as such, and sometimes requires treatment with chemotherapy is not a fully developed malignant cancer. It is not contagious, nor is it believed to be inherited.

About 50 children in the UK develop LCH each year. It can affect children of any age, and is more common in boys than in girls.

LCH is an unusual condition. It has some characteristics of cancer but, unlike almost every other cancer, it may spontaneously resolve in some patients while being life-threatening in others. LCH is classified as a cancer and sometimes requires treatment with chemotherapy. LCH patients are therefore usually treated by children’s cancer specialists (paediatric oncologists/ haematologists).

The vast majority of children will recover completely from LCH.

Histiocytosis was first described in the medical literature in the mid to late 1800s. Through the years, it has been known by various names, such as histiocytosis-X, eosinophilic granuloma, Abt-Letterer-Siwe disease, Hashimoto-Pritzger disease, and Hand-Schüller-Christian syndrome. In 1973, the name Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis (LCH) was introduced. This name was agreed upon to recognize the central role of the Langerhans cell.

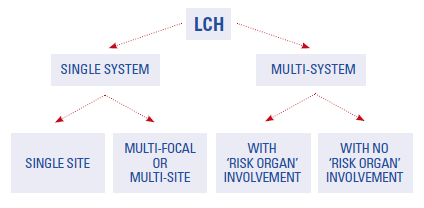

LCH is believed to occur in 1:200,000 children, but any age group can be affected, from infancy through adulthood. In new born and very young infants, it occurs in 1-2 per million. It is, however, believed to be under-diagnosed, since some patients may have no symptoms, while others have symptoms that are mistaken for injury or other conditions. It occurs most often between the ages of 1-3 years and may appear as a single lesion or can affect many body systems, such as skin, bone, lymph glands, liver, lung, spleen, brain, pituitary gland and bone marrow.

Information has been collected in various studies which show that bone involvement occurs in approximately 78% of patients with LCH and often includes the skull (49%), hip/pelvic bone (23%), upper leg bone (17%) and ribs (8%). Skin LCH is seen in as many as 50% of patients. Lung lesions are seen in 20% to 40% of patients, while 30% of patients have lymph node involvement.

Symptoms depend on the location and severity of involvement. It is usually diagnosed with a tissue biopsy, in addition to other testing, such as x-rays and blood studies. A biopsy of an involved site is necessary to make a definitive diagnosis.

While some limited cases of histiocytosis may not require treatment, for patients with more extensive disease, chemotherapy may be necessary. Haematologists and oncologists, who treat cancer, also treat children with Langerhans cell histiocytosis.

Most patients with LCH will survive this disease. LCH in the skin, bones, lymph nodes or pituitary gland usually gets better with treatment and is called “low-risk.” Some patients have involvement in the spleen, liver, bone marrow, lung and skeleton. This is called “high-risk disease” and may be more difficult to treat. Some patients may develop long-term side effects such as diabetes insipidus, stunted growth, loss of teeth, bone defects, hearing loss, or neurologic problems; while other patients remain without side effects. In a minority of cases, the disease can be life-threatening.

Certain factors affect the chance of recovery and options for treatment. These factors include the extent of the disease, whether “risk organs” (liver, spleen, lung, bone marrow) are involved, and how quickly the disease responds to initial treatment.

Patients with LCH should usually have long term follow-up care to detect late complications of the disease or treatment. These may include problems of skeletal deformity or function, liver or lung problems, endocrine abnormalities, dental issues or neurological and neurocognitive dysfunction.

Please be advised that all the information you read here is not a replacement for the advice you will get from your consultant and their team.

LCH1V – A trial looking at improving treatment for children and young people with Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH-IV)

Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH-IV)

Help ensure that we can continue to bring you this vital informational material, make a donation today